Al Jolson

| Al Jolson | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Asa Yoelson |

| Born | May 26, 1886 Srednik, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | October 23, 1950 (aged 64) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Vaudeville Pop standards Jazz Pop |

| Occupations | Actor Comedian Singer |

| Years active | 1911–1950 |

| Labels | Victor, Columbia, Little Wonder, Brunswick, Decca |

| Website | The Al Jolson Society |

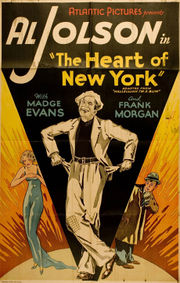

Al Jolson (May 26, 1886 – October 23, 1950) was an American singer, comedian, and actor. He is considered the "first openly Jewish man to become an entertainment star in America", notes PBS. His career lasted from 1911 until his death in 1950, during which time he was commonly dubbed "the world's greatest entertainer”. [1]

His performing style was brash and extroverted, and he popularized a large number of songs that benefited from his "shamelessly sentimental, melodramatic approach".[2] Numerous well-known singers were influenced by his music, including Bing Crosby[3] Judy Garland, rock and country entertainer Jerry Lee Lewis, and Bob Dylan, who once referred to him as "somebody whose life I can feel".[4]

In the 1930s, he was America's most famous and highest paid entertainer.[5] Between 1911 and 1928, Jolson had nine sell-out Winter Garden shows in a row, more than 80 hit records, and 16 national and international tours. Yet he's best remembered today for his leading role in the first (full length) talking movie ever made, The Jazz Singer, released in 1927. He starred in a series of successful musical films throughout the 1930s. After a period of inactivity, his stardom returned with the 1946 Oscar-winning biographical film, The Jolson Story. Larry Parks played Jolson with the songs dubbed in with Jolson’s real voice. A sequel, Jolson Sings Again, was released in 1949, and was nominated for three Oscars. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Jolson became the first star to entertain troops overseas during World War II, and again in 1950 became the first star to perform for GIs in Korea, doing 42 shows in 16 days.

According to the St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, "Jolson was to jazz, blues, and ragtime what Elvis Presley was to rock 'n' roll". Being the first popular singer to make a spectacular "event" out of singing a song, he became a “rock star” before the dawn of rock music. His specialty was building stage runways extending out into the audience. He would run up and down the runway and across the stage, "teasing, cajoling, and thrilling the audience", often stopping to sing to individual members, all the while the "perspiration would be pouring from his face, and the entire audience would get caught up in the ecstasy of his performance".

He enjoyed performing in blackface makeup – a theatrical convention in the mid-19th century. With his unique and dynamic style of singing black music, like jazz and blues, he was later credited with single-handedly introducing African-American music to white audiences.[1] As early as 1911 he became known for fighting against anti-black discrimination on Broadway. Jolson's well-known theatrics and his promotion of equality on Broadway helped pave the way for many black performers, playwrights, and songwriters, including Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, and Ethel Waters.

Early years

Al Jolson was born as Asa Yoelson in Srednik (now known as Seredžius, Lithuania) then in Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire, the fourth child of Moses Reuben Yoelson and his wife Naomi. His siblings were Rose, Etta, Hirsch (Harry), and a sister who died in infancy. Moses Yoelson moved to the United States in 1891, and was able to find a job as a rabbi and cantor at the Talmud Torah Synagogue in the Southwest Waterfront neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Three years later, his family would join him.

Hard times hit the family when his mother, Naomi, died in late 1894. Following his mother's death, young Asa was in a state of withdrawal for seven months. Upon being introduced to show business in 1895 by entertainer Al Reeves, Asa and Hirsch became fascinated by the industry, and by 1897, the brothers were singing for coins on local street corners, using the names "Al" and "Harry". They would usually use the money to buy tickets to shows at the National Theater.[1] Asa and Hirsch spent most of their days working different jobs as a team.[6]:23-40

Stage performer

Burlesque and vaudeville

In the spring of 1902, he accepted a job with Walter L. Maim's Circus. Although he had been hired as an usher, Maim was impressed by Jolson's singing voice and gave him a position as a singer during the circus' Indian Medicine Side Show segment.[6]:49-50

By the end of the year, however, the circus had folded, and Jolson was again out of work. In May 1903, the head producer of the burlesque show, Dainty Duchess Burlesquers, agreed to give Jolson a part in one show. Asa gave a remarkable performance of "Be My Baby Bumble Bee", and the producer agreed to keep him for future shows. Unfortunately, the show closed by the end of the year. Asa was able to avoid financial troubles by forming a vaudeville partnership with his brother Hirsch, now a vaudeville performer who was known as Harry Yoelson. The brothers worked for the William Morris Agency.[6]:50-60

Asa and Harry also eventually were teamed with Joe Palmer. During their time with Palmer, they were able to get bookings in a nationwide tour. However, live performances were fading in popularity, as nickelodeon theaters captured audiences; by 1908, nickelodeon theaters were completely dominant throughout New York City as well. While performing in a Brooklyn theater in 1904,[7] Al decided on a new approach and began wearing blackface makeup. The conversion to blackface boosted his career and he began wearing blackface in all of his shows.[6]:61-80

In the fall of 1905, Harry left the trio, following a harsh argument with Al. Harry had refused Al's request to take care of Joe Palmer — who was in a wheelchair — while he went out on a date. After Harry's departure, Al and Joe Palmer worked as a duo, but were not very successful together. By 1906,[7] the two agreed to separate, and Jolson was on his own.[6]:68-70

Al became a regular at the Globe and Wigwam Theater in San Francisco, California, and remained successful nationwide as a vaudeville singer[7] He took up residence in San Francisco, saying the earthquake-devastated area needed someone to cheer them up. In 1908, Jolson — needing money for himself and his new wife Henrietta — returned to New York. In 1909, Al's singing caught the attention of Lew Dockstader, who was the producer and star of Dockstader's Minstrels. Al accepted Dockstader's offer, and became a regular blackface performer.[6]:70-81

Broadway playhouses

Winter Garden Theater

According to Esquire magazine, "J. J. Shubert, impressed by Jolson’s overpowering display of energy, booked him for La Belle Paree, a musical comedy which opened at the Winter Garden in 1911. Within a month Jolson was a star. From then until 1926, when he retired from the stage, he could boast an unbroken series of smash hits."[8]

On March 20, 1911, Jolson starred in his first play at the Winter Garden Theater in New York City, La Belle Paree, which also greatly helped launch his career as a singer. The opening night drew a huge crowd to the theater, and that evening Jolson gained audience popularity by singing old Stephen Foster songs in blackface. In the wake of that phenomenal opening night, Jolson was given a position in the show's cast. The show closed after 104 performances, and during its run Jolson's popularity grew greatly. Following La Belle Paree, Jolson accepted an offer to perform in the play Vera Violetta. The show opened on November 20, 1911, and, like La Belle Paree, was a phenomenal success. In the show, Jolson again portrayed the role of a blackface singer, and managed to become so popular, that his weekly salary- which he earned from his success in La Belle Paree- of $500 was increased to $750.[6]:98-117

After Vera Violetta ran its course, Jolson starred in The Whirl of Society, and through this play, his career on Broadway would rise to new heights. During his time at the Winter Garden, Jolson would tell the audience "you ain't heard nothing yet" before performing additional songs. In the play, Jolson debuted his signature blackface character, "Gus."[7] The play was so successful, that Winter Garden owner Lee Shubert agreed to sign Jolson to a seven year contract with a salary of $1,000 a week. Jolson would reprise his role as "Gus" in future plays and by 1914, Jolson achieved so much popularity with the theater audience that his $1,000 a week salary was doubled to $2,000 a week. In 1916, Robinson Crusoe, Jr. was the first play where he was featured as the star character. In 1918, Jolson's acting career would be pushed even further, after he starred in the hit play Sinbad.[6]:123-141

1919 "Swanee" sheet music with Jolson on the cover. For the full sheet music, see Wikisource.

|

It became the most successful Broadway play of 1918 and 1919. A new song was later added to the show that would become composer George Gershwin's first hit recording, "Swanee". Jolson also added another song to the show, "My Mammy". By 1920, Jolson had become the biggest star on Broadway.[6]:143-147

Jolson's own theater

His next play, Bombo, would also take his career to new heights and became so successful that it went beyond Broadway and held performances nationwide.[6]:171 It also led Lee Shubert to rename his newly built theater, which was across from Central Park, as Jolson's Fifty-ninth Street Theatre. Aged 35, Jolson became the youngest man in American history to have a theatre named after him.[9]:117

But on the opening night of Bombo, and the first performance at the new theatre, he suffered from extreme stage fright, walking up and down the streets for hours before showtime. Out of fear, he lost his voice backstage and begged the stagehands not to raise the curtains. But when the curtains went up, he "was [still] standing in the wings trembling and sweating". After being physically shoved onto the stage by his brother Harry, he performed and received an ovation that he would never forget: "For several minutes, the applause continued while Al stood and bowed after the first act". He refused to go back on stage for the second act, but the audience "just stamped its feet and chanted 'Jolson, Jolson', until he came back out." He took thirty-seven curtain calls that night, and told the audience "I'm a happy man tonight."[9]:118

In March, 1922, he moved the production to the larger Century Theater for a special benefit performance to aid injured Jewish veterans of World War I.[10] After taking the show on the road for a season, he returned in May, 1923, to perform Bombo at "his first love", the Winter Garden. The reviewer for the New York Times wrote, "He returned like the circus, bigger and brighter and newer than ever. ... Last night's audience was flatteringly unwilling to go home, and when the show proper was over, Jolson reappeared before the curtain and sang more songs, old and new."[11]

"I don’t mind going on record as saying that he is one of the few instinctively funny men on our stage", wrote reviewer Charles Darnton in the New York Evening World. "Everything he touches turns to fun. To watch him is to marvel at his humorous vitality. He is the old-time minstrel man turned to modern account. With a song, a word, or even a suggestion he calls forth spontaneous laughter. And here you have the definition of a born comedian."[9]:87

Performing in blackface

Performing in blackface makeup was a theatrical convention used by many entertainers at the beginning of the 20th century, having its origin in the minstrel show.[12] Al Jolson was the most famous performer to wear blackface makeup when singing.[12] Working behind a blackface mask "gave him a sense of freedom and spontaneity he had never known"[7] According to film historian Eric Lott, for the white minstrel man "to put on the cultural forms of 'blackness' was to engage in a complex affair of manly mimicry...To wear or even enjoy blackface was literally, for a time, to become black, to inherit the cool, virility, humility, abandon, or gaité de coeur that were the prime components of white ideologies of black manhood."[13]:52

Frederick Douglass is said to have abhorred blackface performances and wrote against the institution of blackface minstrelsy, condemning it as racist in nature, with inauthentic, northern, white origins.[14] Some authors note that the blackface used in 19th century minstrel shows caricatured and stereotyped the black man with images that may have remained in the minds of white audiences for decades.[15] Today the practice is associated with racial stereotyping and no longer used in stagecraft.[12]

As metaphor of mutual suffering

Jazz historians have described Jolson’s blackface and singing style as metaphors for Jewish and black suffering throughout history. Jolson’s first film, The Jazz Singer, for instance, is described by historian Michael Alexander as an expression of the liturgical music of Jews with the "imagined music of African Americans," noting that "prayer and jazz become metaphors for Jews and blacks."[16]:176 Playwright Samson Raphaelson, after seeing Jolson perform his stage show, "Robinson Crusoe," stated that "he had an epiphany: 'My God, this isn’t a jazz singer,' he said. 'This is a cantor!'" The image of the blackfaced cantor remained in Raphaelson’s mind when he conceived of the story which led to The Jazz Singer.[17]:502

Upon release of the film, the first full-length sound picture, film reviewers saw the symbolism and metaphors portrayed by Jolson in his role as the son of a cantor wanting to become a "jazz singer":

- "Is there any incongruity in this Jewish boy with his face painted like a Southern Negro singing in the Negro dialect? No, there is not. Indeed, I detected again and again the minor key of Jewish music, the wail of the Chazan, the cry of anguish of a people who had suffered. The son of a line of rabbis well knows how to sing the songs of the most cruelly wronged people in the world’s history."[17]:502

According to Alexander, East European Jews were uniquely qualified to understand the music, noting how Jolson himself made the comparison of Jewish and African American suffering in a new land in his film "Big Boy": In a blackface portrayal of a former slave, he leads a group of recently freed slaves, played by black actors, in verses of the classic slave spiritual "Go Down Moses." One reviewer of the film expressed how Jolson’s blackface added significance to his role:

- "When one hears Jolson’s jazz songs, one realizes that jazz is the new prayer of the American masses, and Al Jolson is their cantor. The Negro makeup in which he expresses his misery is the appropriate talis [prayer shawl] for such a communal leader."[16]:176

Relations with blacks

Jolson first heard African-American music, such as jazz, blues, and ragtime, played in the back alleys of New Orleans, Louisiana. He enjoyed singing the new jazz-style of music, and it's not surprising that he often performed in blackface, especially songs he made popular, like Swanee, My Mammy, and Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody. In most of his movie roles, however, including a singing hobo in Hallelujah, I'm a Bum or a jailed convict in Say It With Songs, he chose to act without using blackface. In the 1927 film The Jazz Singer, he performed only a few songs, including My Mammy, in blackface, although there was nothing in the storyline that required a black singer.

As a Jewish immigrant and America's most famous and highest paid entertainer, he may have had the incentive and resources to help break down racial attitudes. For instance, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) during its peak in the early 1920s, included about 15% of the nation's eligible voting population, 4-5 million men.[18] While D.W. Griffith created the blockbuster movie The Birth of a Nation, which glorified white supremacy and the KKK, Jolson chose to star in The Jazz Singer, which defied racial bigotry by introducing American black music to white audiences worldwide.[1]

While growing up, he had many black friends, including Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson, who later became a legendary tap dancer."[8] As early as 1911, at the age of 25, he was already noted for fighting discrimination on the Broadway stage and later in his movies:[19]

- "at a time when black people were banned from starring on the Broadway stage,"[20] he promoted the play by black playwright Garland Anderson,[21] which became the first production with an all-black cast ever produced on Broadway;

- he brought an all-black dance team from San Francisco that he tried to feature in his Broadway show;[19]

- he demanded equal treatment for Cab Calloway with whom he performed a number of duets in his movie The Singing Kid.

- he was "the only white man allowed into an all black nightclub in Harlem;"[19]

- he once read in the newspaper that songwriters Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, neither of whom he had ever heard of, were refused service at a Connecticut restaurant because of their race. He immediately tracked them down and took them out to dinner "insisting he'd punch anyone in the nose who tried to kick us out!" [22]

Jeni LeGon, a black female tap dance star,[23] recalls her life as a film dancer: "But of course, in those times it was a 'black-and-white world.' You didn't associate too much socially with any of the stars. You saw them at the studio, you know, nice — but they didn't invite. The only ones that ever invited us home for a visit was Al Jolson and Ruby Keeler."[24] Brian Conley, former star of the 1995 British play Jolson, stated during an interview, "I found out Jolson was actually a hero to the black people of America. At his funeral, black actors lined the way, they really appreciated what he’d done for them."[25] Noble Sissle, then president of the Negro Actors' Guild, represented that organization at his funeral.[26]

Jolson's physical expressiveness also affected the music styles of some black performers. Music historian Bob Gulla writes that "the most critical influence in Jackie Wilson's young life was Al Jolson." He points out that Wilson's ideas of what a stage performer could do to keep their act an "exciting" and "thrilling performance" was shaped by Jolson's acts, "full of wild writhing and excessive theatrics." Wilson felt that Jolson, along with Louis Jordan, another of his idols, "should be considered the stylistic forefathers of rock and roll."[27]

According to the St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture: "Almost single-handedly, Jolson helped to introduce African-American musical innovations like jazz, ragtime, and the blues to white audiences.... [and] paved the way for African-American performers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, and Ethel Waters.... to bridge the cultural gap between black and white America."[1] Jazz historian Amiri Baraka wrote, "the entrance of the white man into jazz...did at least bring him much closer to the Negro." He points out that "the acceptance of jazz by whites marks a crucial moment when an aspect of black culture had become an essential part of American culture."[28]:151

In a recent interview, Clarence 'Frogman' Henry, one of the most popular and respected jazz singers of New Orleans, said, "Jolson? I loved him. I think he did wonders for the blacks and glorified entertainment."[29]:307

Personal life

Politics

Jolson was a political and economic conservative, supporting both Warren G. Harding in 1920 and Calvin Coolidge in 1924 for president of the United States. As "one of the biggest stars of his time, [he] worked his magic singing Harding, You're the Man for Us to enthralled audiences ... [and] was subsequently asked to perform Keep Cool with Coolidge four years later. ... Jolson, like the men who ran the studios, was the rare showbiz Republican."[30] He was unlike most other Jewish performers, who supported the losing Democratic candidate, John William Davis. Jolson did, however, publicly campaign for Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932.[6]:241

Married life

In 1906, while living in San Francisco, Jolson met dancer Henrietta Keller, and the two engaged in a year-long relationship before marrying in September 1907.[7] In 1918, however, Henrietta — tired of what she reputedly considered his womanizing and refusal to come home after shows — filed for divorce. In 1920, Jolson began a relationship with Broadway actress Alma Osbourne (known professionally as Ethel Delmar); the two were married in August 1922.[6]:256

Ruby Keeler

In the summer of 1928, Jolson met tap dancer, and later successful actress, Ruby Keeler at Texas Guinan's night club and was dazzled by her on sight; at the club, the two danced together. Three weeks later, Jolson saw a production of George M. Cohan's Rise of Rosie O'Reilly, and noticed she was in the show's cast. Now knowing she was going about her Broadway career, Jolson attended another one of her shows, Show Girl, and rose from the audience and engaged in her duet of "Liza". After this moment, the show's producer, Florenz Ziegfeld, asked Jolson to join the cast and continue to sing duets with Keeler. Jolson accepted Ziegfeld's offer and during their tour with Ziegfeld, the two started dating and were married on September 21, 1928. In 1935, Al and Ruby adopted a son, whom they named "Al Jolson Jr."[7] In 1939, however — despite a marriage that was considered to be more successful than his previous ones, Keeler left Jolson, and later married John Lowe, with whom she would have four children and remain married until his death.[6]:223-259[7]

Erle Galbraith

In 1944, while giving a show at a military hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Jolson met a young X-ray technician, Erle Galbraith. Jolson became fascinated by her and – over a year after meeting – was able to track her down and hired her as an actress while he served as a producer at Columbia Pictures. After Jolson, whose health was still scarred from his previous battle with malaria, was hospitalized in the winter of 1945, Erle visited him and the two quickly began a relationship. They were married on March 22, 1945. During their marriage, the Jolsons adopted two children, Asa Jr. (b. 1948) and Alicia (b. 1949),[7] and remained married until Al's death in 1950.[6]:293-298

After a year and a half of marriage, his new wife had actually never seen him perform in front of an audience, and the first occasion came unplanned. As told by actor comedian Alan King, it happened during a dinner by the New York Friars' Club at the Waldorf Astoria in 1946, honoring the career of Sophie Tucker. Jolson and his wife were in the audience along with a thousand others, and George Jessel was emcee. He asked Al, privately, to perform at least one song. Jolson replied, "No, I just want to sit here." Then later, without warning, during the middle of the show, Jessel says, "Ladies and gentlemen, this is the easiest introduction I ever had to make. The world's greatest entertainer, Al Jolson." King recalls what happened next:

The place is going wild. Jolson gets up, takes a bow, sits down. . . people start banging with their feet, and he gets up, takes another bow, sits down again. It's chaos, and slowly, he seems to relent. He walks up onto the stage . . . kids around with Sophie and gets a few laughs, but the people are yelling, 'Sing! Sing! Sing!' . . . Then he says, 'I'd like to introduce you to my bride,' and this lovely young thing gets up and takes a bow. The audience doesn't care about the bride, they don't even care about Sophie Tucker. 'Sing! Sing! Sing!' they're screaming again.My wife has never seen me entertain, Jolson says, and looks over toward Lester Lanin, the orchestra leader: 'Maestro, Is it True What They Say About Dixie?'[31]

Closeness with his brother Harry

Despite their close relationship growing up, Harry did show some disdain for Al's success over the years. Even during their time with Jack Palmer, Al was rising in popularity while Harry was fading. After separating from Al and Jack, Harry's career in show business, however, sank greatly. On one occasion — which was another factor in his on-off relationship with Al — Harry offered to be Al's agent, but Al rejected the offer, worried about the pressure that he would have faced from his producers for hiring his brother as his agent. Shortly after Harry's wife Lillian died in 1948, Harry and Al became close once again.[6]:318-324

Movies

The Jazz Singer

In the first part of the 20th century, Al Jolson was without question the most popular performer on Broadway and in vaudeville. Show-business historians regard him as a legendary institution. Yet for all his success in live venues, Al Jolson is possibly best remembered today for his numerous recordings and for starring in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first nationally distributed feature film that included dialogue sequences as well as music and sound effects.

Jolson had actually starred in a talking film before The Jazz Singer: a 1926 short subject titled A Plantation Act. This simulation of a stage performance by Jolson was originally presented in a program of musical shorts, demonstrating the Vitaphone sound-film process. A Plantation Act was not preserved for posterity and was considered lost as early as 1933; see the Wikipedia entry for A Plantation Act for details about the film's restoration.

Music historian John Shepherd, discussing The Jazz Singer, notes that the title "reflected the contemporary popularity of the idea of jazz, but not its actuality. . . . and had no direct connection with the kind of performance that could then be found in clubs, dance halls and theaters."[32]

Warner Bros. had originally picked George Jessel for the role, as he had starred in the Broadway play. However, Jessel refused the offer and Jack L. Warner then offered the role to Jolson, who, according to Jessel, also helped finance the film.[33]

- Story synopsis

A New York Times review of the movie in 1927 described the basic storyline: "There is naturally a good deal of sentiment attached to the narrative, which is one wherein Cantor Rabinowitz is eager that his son Jakie shall become a cantor" and carry on five generations of family traditions. "The old man’s anger is aroused when one night he hears that Jakie has been singing jazz songs in a saloon. The boy’s heart and soul are with the modern music. He runs away from home and tours the country until, through a friend he is engaged by a New York producer to sing in the Winter Garden," a major theater on Broadway.[34]

But an unfortunate set of coincidences then take place: the opening of his first Broadway show is also on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Then, on the day of the show, he learns that his father is seriously ill, so returns home to find him on his deathbed, imploring him to take his place at the synagogue as cantor for the holiday service. After a tormenting emotional tug-of-war between his desire for stardom, his family, and religious tradition, he chooses to perform the evening service at the synagogue in place of his father.

Having no choice, the Broadway show's producer had postponed the show for the next evening, and Jakie went on to become a smash success. Writer Neal Gabler called the story "an assimilationist fable," but the story was "close to the true story of Al Jolson," notes author Helen Epstein, "as well as a paradigm for a generation of sons of all kinds of immigrants."[35]

The movie premiere

Harry Warner's daughter, Doris Warner, remembered the opening night, and said that when the picture started she was still crying over the loss of her beloved uncle Sam, who was planning to be there but died suddenly, at the age of 40, the day before. But halfway through the eighty-nine minute movie she began to be overtaken by a sense that something remarkable was happening. Jolson's 'Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain't heard nothin' yet...' provoked shouts of pleasure and applause. After each Jolson song, the audience applauded. Excitement mounted as the film progressed, and when Jolson began his scene with Eugenie Besserer, "the audience became hysterical."[36]:129

According to film historian Scott Eyman, "by the film's end, the Warner brothers had shown an audience something they had never known, moved them in a way they hadn't expected. The tumultuous ovation at curtain proved that Jolson was not merely the right man for the part of Jackie Rabinowitz, alias Jack Robin; he was the right man for the entire transition from silent fantasy to talking realism. The audience, transformed into what one critic called, 'a milling, battling mob' stood, stamped, and cheered 'Jolson, Jolson, Jolson!'"[36]:140

At the end of the film, Jolson rose from his seat and ran down to the stage. "God, I think you're really on the level about it. I feel good" he cried to the audience. Stanley Watkins would always remember Jolson signing autographs after the show, tears streaming down his face. May McAvoy, Jolson's costar remembered that "[the] police were there to control the crowds. It was a very big thing, like The Birth of a Nation."

Introduction of sound

The film was produced by Warner Bros., using its revolutionary Vitaphone sound process. Vitaphone was originally intended for musical renditions, and The Jazz Singer follows this principle, with only the musical sequences using live sound recording. The moviegoers were electrified when the silent actions were interrupted periodically for a song sequence with real singing and sound. Jolson's dynamic voice, physical mannerisms, and charisma held the audience spellbound.

Costar May McAvoy, according to author A. Scott Berg, could not help sneaking into theaters day after day as the film was being run. "She pinned herself against a wall in the dark and watched the faces in the crowd. In that moment just before 'Toot, Toot, Tootsie,' she remembered, 'A miracle occurred. Moving pictures really came alive. To see the expressions on their faces, when Joley spoke to them . . . you'd have thought they were listening to the voice of God.'"[37] "Everybody was mad for the talkies," said movie star Gregory Peck in a Newsweek interview. "I remember 'The Jazz Singer,' when Al Jolson just burst into song, and there was a little bit of dialogue. And when he came out with 'Mammy,' and went down on his knees to his Mammy, it was just dynamite."[38]

This opinion is shared by Mast and Kawin:

...this moment of informal patter at the piano is the most exciting and vital part of the entire movie...when Jolson acquires a voice, the warmth, the excitement, the vibrations of it, the way its rambling spontaneity lays bare the imagination of the mind that is making up the sounds ...[and] the addition of a Vitaphone voice revealed the particular qualities of Al Jolson that made him a star. Not only the eyes are a window on the soul.[39]:231

Jewish meanings

Cultural historian Linda Williams notes that "The Jazz Singer represents the triumphs of the assimilating son over the old-world father ... and present impediments to an assimilating show-biz success....[and] when Jakie's father says, 'Stop', the flow of "jazz" music (and spontaneous speech) freezes. But the Jewish mother recognizes the virtue of the old world in the new and the music flows again."[40]:186 According to film historian Robert Carringer, even the father eventually comes to understand that his son's jazz singing is "fundamentally an ancient religious impulse seeking expression in a modern, popular form".[41]:23 Or as the film itself states in its first title card, "perhaps this plaintive, wailing song of jazz is, after all, the misunderstood utterance of a prayer."[41]

Film historian Scott Eyman also describes the cultural perspective of the film:

[It] marks one of the few times Hollywood Jews allowed themselves to contemplate their own central cultural myth, and the conundrums that go with it... The Jazz Singer implicitly celebrates the ambition and drive needed to escape the shtetls of Europe and the ghettos of New York, and the attendant hunger for recognition. Jack, Sam, and Harry let Jack Robin have it all: the satisfaction of taking his father's place and of conquering the Winter Garden. They were, perhaps unwittingly, dramatizing some of their own ambivalence about the debt first-generation Americans owed their parents.[36]:142

Other feature films

- The Singing Fool (1928)

With Warner Bros., Al Jolson made his first "all-talking" picture, The Singing Fool (1928) — the story of a driven entertainer who insisted upon going on with the show even as his small son lay dying, and its signature tune, "Sonny Boy," became the first American record to sell one million copies. The film was even more popular than The Jazz Singer, and held the record for box-office attendance for 10 years, until broken by Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Jolson continued to make features for Warner Bros., very similar in style to The Singing Fool, Say It with Songs (1929), Mammy (1930), and Big Boy (1930). A restored version of Mammy, which includes Jolson in some Technicolor sequences, was first screened in 2002.[42] (Jolson's first Technicolor appearance was in a cameo in the musical Show Girl in Hollywood (1930) from First National Pictures, a Warner Bros. subsidiary.) The sameness of the stories, Jolson's large salary, and changing public tastes in musicals contributed to the films' diminishing returns over the next few years. As a result of this, Jolson decided to return to Broadway, and starred in a new show, entitled Wonder Bar, which was not very successful.[6]:231-235

Hallelujah, I'm a Bum/Hallelujah, I'm a Tramp

Despite these new troubles, Jolson was able to make a comeback after performing a hit concert in New Orleans after "Wonderbar" closed in 1931. Warners allowed him to make one film with United Artists, Hallelujah, I'm a Bum, in 1933 (the film had to be retitled Hallelujah, I'm a Tramp in the UK and other English-speaking countries where 'bum' means 'butt' and where the slang word for a vagrant is 'tramp' rather than 'bum'). It was directed by Lewis Milestone and written by noted screenwriter Ben Hecht. Hecht was also active in the promotion of civil rights: "Hecht film stories featuring black characters included Hallelujah, I'm a Bum, co-starring Edgar Conner as Al Jolson's sidekick, in a politically savvy rhymed dialogue over Richard Rodgers music."[43]

As the title suggests, the film was a direct response to the Great Depression, with messages to his vagabond friends equivalent to "there's more to life than money" and "the best things in life are free". A New York Times review wrote, "The picture, some persons may be glad to hear, has no Mammy song. It is Mr. Jolson's best film and well it might be, for that clever director, Lewis Milestone, guided its destiny.... a combination of fun, melody and romance, with a dash of satire..."[44] Another review added, "A film to welcome back, especially for what it tries to do for the progress of the American musical..."[45]

Wonder Bar (1934)

In 1934, he starred in a movie version of his earlier stage play, Wonder Bar, and co-starred Kay Francis, Dolores del Río, Ricardo Cortez, and Dick Powell. The movie is a "musical Grand Hotel, set in the Parisian nightclub owned by Al Wonder (Jolson). Wonder entertains and banters with his international clientele."[46]:97

Reviews were generally positive: "Wonder Bar has got about everything. Romance, flash, dash, class, color, songs, star-studded talent and almost every known requisite to assure sturdy attention and attendance... It's Jolson's comeback picture in every respect.";[47] and, "Those who like Jolson should see Wonder Bar for it is mainly Jolson; singing the old reliables; cracking jokes which would have impressed Noah as depressingly ancient; and moving about with characteristic energy."[48] Returning to Warners, Jolson bowed to new production ideas, focusing less on the star and more on elaborately cinematic numbers staged by Busby Berkeley and Bobby Connolly. This new approach worked, sustaining Jolson's movie career until the Warner contract lapsed in 1935. Jolson co-starred with his actress-dancer wife, Ruby Keeler, only once, in Go Into Your Dance.

The Singing Kid (1936)

Jolson's last Warner vehicle was The Singing Kid (1936), a parody of Jolson's stage persona (he plays a character named Al Jackson) in which he pokes fun at his stage histrionics and taste for "mammy" songs—the latter via a number by E. Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen titled "I Love to Singa", and a comedy sequence with Jolson doggedly trying to sing "Mammy" while The Yacht Club Boys keep telling him such songs are outdated.[29]

According to jazz historian Michael Alexander, Jolson had once griped that "People have been making fun of Mammy songs, and I don't really think that it's right that they should, for after all, Mammy songs are the fundamental songs of our country." In this film, he notes, "Jolson had the confidence to rhyme 'Mammy' with 'Uncle Sammy'", adding "Mammy songs, along with the vocation 'Mammy singer', were inventions of the Jewish Jazz Age."[16]:136

The film also gave a boost to the career of black singer and bandleader Cab Calloway, who performed a number of songs alongside Jolson. In his autobiography, Calloway writes about this episode:

I'd heard Al Jolson was doing a new film on the Coast, and since Duke Ellington and his band had done a film, wasn't it possible for me and the band to do this one with Jolson. Frenchy got on the phone to California, spoke to someone connected with the film and the next thing I knew the band and I were booked into chicago on our way to California for the film, The Singing Kid. We had a hell of a time, although I had some pretty rough arguments with Harold Arlen, who had written the music. Arlen was the songwriter for many of the finest Cotton Club revues, but he had done some interpretations for The Singing Kid that I just couldn't go along with. He was trying to change my style and I was fighting it. Finally, Jolson stepped in and said to Arlen, 'Look, Cab knows what he wants to do; let him do it his way.' After that, Arlen left me alone. And talk about integration: Hell, when the band and I got out to Hollywood, we were treated like pure royalty. Here were Jolson and I living in adjacent penthouses in a very plush hotel. We were costars in the film so we received equal treatment, no question about it.[49]:131

The Singing Kid was not one of the studio's major attractions, (it went out under the subsidiary First National trademark,) and Jolson didn't even rate star billing. The song "I Love to Singa" later appeared in Tex Avery's cartoon of the same name. The movie also became the first important role for future child star Sybil Jason in a scene directed by Busby Berkeley. Jason remembers that Berkeley worked on the film although he is not credited.[46]:103

Rose of Washington Square (1939)

His next movie — his first with Twentieth Century-Fox — was Rose of Washington Square, in 1939. It starred Jolson, Alice Faye and Tyrone Power, and included many of Jolson's most well-known songs, although a number of songs were cut to shorten the movie's length, including "April Showers" and "Avalon". Reviewers wrote, "Mr Jolson's singing of Mammy, California, Here I Come and others is something for the memory book."[50] and "Of the three co-stars this is Jolson's picture ... because it's a pretty good catalog in anybody's hit parade."[51] The movie was released on DVD in October 2008. Twentieth Century-Fox hired him to re-create a scene from The Jazz Singer in the Alice Faye-Don Ameche film Hollywood Cavalcade. Guest appearances in two more Fox films followed that same year, but Jolson never starred in a full-length feature film again.

The Jolson Story

After the success of the George M. Cohan film biography, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Hollywood columnist Sidney Skolsky believed that a similar film could be made about Al Jolson—and he knew just where to pitch the project. Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures, loved the music of Al Jolson. He knew that Jolson had been one of America's most well-known and popular entertainers.

Skolsky pitched the idea of an Al Jolson biopic and Cohn agreed. It was directed by Alfred E. Green (best known today for the pre-Code masterpiece Baby Face), with musical numbers staged by Joseph H. Lewis. With Jolson providing almost all the vocals, and veteran Columbia contractee Larry Parks playing Jolson, The Jolson Story (1946) became one of the biggest hits of the year.[52]

Larry Parks wrote, in a personal tribute to Jolson, "Stepping into his shoes was, for me, a matter of endless study, observation, energetic concentration to obtain, perfectly if possible, a simulation of the kind of man he was. It is not surprising, therefore, that while making The Jolson Story, I spent 107 days before the cameras and lost eighteen pounds in weight."[53] From a review in Variety, "But the real star of the production is that Jolson voice and that Jolson medley. It was good showmanship to cast this film with lesser people, particularly Larry Parks as the mammy kid... As for Jolson's voice, it has never been better. Thus the magic of science has produced a composite whole to eclipse the original at his most youthful best."[54]

Parks received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, and the film became one of the highest-grossing films of the year. Although Jolson was too old to play himself in the film, he persuaded the studio to let him appear in one musical sequence, "Swanee", shot entirely in long shot, with Jolson in blackface singing and dancing onto the runway leading into the middle of the theater. In the wake of the film's success, Jolson became a top singer among the American public once again.[6]:311 Decca Records signed Jolson and he recorded for Decca until his death.

Critical observations

According to film historian Krin Gabbard, The Jolson Story goes further than any of the earlier films in exploring the significance of blackface and the relationships that whites have developed with blacks in the area of music. To him, the film seems to imply an inclination of white performers, like Jolson, who are possessed with "the joy of life and enough sensitivity, to appreciate the musical accomplishments of blacks".[55]:53 To support his view he describes a significant part of the movie:

While wandering around New Orleans before a show with Dockstader's Minstrels, he enters a small club where a group of black jazz musicians are performing. "Jolson has a revelation, that the staid repertoire of the minstrel troupe can be transformed by actually playing black music in blackface. He tells Dockstader that he wants to sing what he has just experienced: 'I heard some music tonight, something they call jazz. Some fellows just make it up as they go along. They pick it up out of the air.' After Dockstader refuses to accommodate Jolson's revolutionary concept, the narrative chronicles his climb to stardom as he allegedly injects jazz into his blackface performances ... Jolson's success is built on anticipating what Americans really want. Dockstader performs the inevitable function of the guardian of the status quo, whose hidebound commitment to what is about to become obsolete reinforces the audience's sympathy with the forward-looking hero."[55]:54

This has been a theme which was traditionally "dear to the hearts of the men who made the movies."[55]:54 Film historian George Custen describes this "common scenario, in which the hero is vindicated for innovations that are initially greeted with resistance ... [T]he struggle of the heroic protagonist who anticipates changes in cultural attitudes is central to other white jazz biopics such as The Glenn Miller Story (1954) and The Benny Goodman Story (1955)".[56]:147 "Once we accept a semantic change from singing to playing the clarinet, The Benny Goodman Story becomes an almost transparent reworking of The Jazz Singer ... and The Jolson Story."[55]:54

Jolson Sings Again

The Jolson Story and its sequel Jolson Sings Again (1949) introduced a new generation to Jolson. Jolson Sings Again opened at Loew's State Theatre in New York with positive reviews: "Mr. Jolson's name is up in lights again and Broadway is wreathed in smiles", wrote Thomas Pryor in The New York Times. "That's as it should be, for Jolson Sings Again is an occasion which warrants some lusty cheering ...".[9]:287 Jolson did a tour of New York film theaters to plug the movie, traveling with a police convoy to make timetables for all showings, often ad libbing jokes and performing songs for the audience. Extra police were on duty as crowds jammed the streets and sidewalks at each theater Jolson visited.[9]:286-287 In Chicago, a few weeks later, he sang to 100,000 people at Soldier Field, and later that night appeared at the Oriental Theatre with George Jessel where 10,000 people had to be turned away.[9]:287

In Baltimore, Maryland, he took his wife Erle to see St Mary's Catholic School where he was confined for a while as a boy and treated for tuberculosis. He introduced her to the same priest, Father Benjamin, who watched over him. That night, Jolson took over two hundred of the church's kids to see Jolson Sings Again at the Hippodrome Theatre. A few weeks later, the Jolsons were received by President Harry Truman at the White House.

Radio shows

Jolson, who had been a popular guest star on radio since its earliest days, got his own show, hosting the Kraft Music Hall from 1947 to 1949, with Oscar Levant as a sardonic, piano-playing sidekick. Despite such singers as Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Perry Como being in their primes, Jolson was voted the "Most Popular Male Vocalist" in 1948 by a poll in the show biz newspaper Variety.

The next year, Jolson was named "Personality of the Year" by the Variety Clubs of America. When Jolson appeared on Bing Crosby's radio show, he attributed his receiving the award to his being the only singer not to make a record of Mule Train, which had been a widely covered hit of that year (four different versions, one of them by Crosby, had made the top ten on the charts). Jolson even joked that he had tried to sing the hit song: "I got the clippetys all right, but I can't clop like I used to."

Planned television and movie

When Jolson appeared on Steve Allen's KNX Los Angeles radio show in 1949 to promote Jolson Sings Again, he offered his curt opinion of the burgeoning television industry: "I call it smell-evision." Writer Hal Kanter recalled that Jolson's own idea of his television debut would be a corporate-sponsored, extra-length spectacular that would feature him as the only performer, and would be telecast without interruption. In 1950, it was announced that Jolson agreed to appear on the CBS television network. However, he died before production could be initiated. In 1950, Columbia was thinking about a third Jolson musical, and this time Jolson would play himself. The project, tentatively titled You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet, was to dramatize Jolson's recent tours of military bases. The film was never made.

World War II and Korean War tours

World War II

Japanese bombs on Pearl Harbor shook Jolson out of continuing moods of lethargy due to years of little activity and "... he dedicated himself to a new mission in life.... Even before the U.S.O. began to set up a formal program overseas, the excitable Jolson was deluging War and Navy Department brass with phone calls and wires. He demanded permission to go anywhere in the world where there is an American serviceman who wouldn’t mind listening to ‘Sonny Boy’ or ‘Mammy’.... [and] early in 1942, Jolson became the first star to perform at a GI base in World War II".[57]:43-44

From a New York Times interview in 1942: "When the war started... [I] felt that it was up to me to do something, and the only thing I know is show business. I went around during the last war and I saw that the boys needed something besides chow and drills. I knew the same was true today, so I told the people in Washington that I would go anywhere and do an act for the Army."[58] Shortly after the war began, he wrote a letter to Steven Early, press secretary to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, volunteering "to head a committee for the entertainment of soldiers and said that he "would work without pay... [and] would gladly assist in the organization to be set up for this purpose". A few weeks later, he received his first tour schedule from the newly formed United Services Organization (USO), "the group his letter to Early had helped create".[9]:253

He did as many as four shows a day in the jungle outposts of Central America and covered the string of U.S. Naval bases. He paid for part of the transportation out of his own pocket. Upon doing his first, and unannounced, show in England in 1942, the reporter for the Hartford Courant wrote, "... it was a panic. And pandemonium... when he was done the applause that shook that soldier-packed room was like bombs falling again in Shaftsbury Avenue."[59]

From an article in the New York Times: "He [Jolson] has been to more Army camps and played to more soldiers than any other entertainer. He has crossed the Atlantic by plane to take song and cheer to the troops in Britain and Northern Ireland. He has flown to the cold wastes of Alaska and the steaming forests of Trinidad. He has called at Dutch‑like Curaçao. Nearly every camp in this country has heard him sing and tell funny stories."[58] Some of the unusual hardships of performing to active troops were described in an article he wrote for Variety, in 1942: "In order to entertain all the boys ... it became necessary for us to give shows in foxholes, gun emplacements, dugouts, to construction groups on military roads; in fact, any place where two or more soldiers were gathered together, it automatically became a Winter Garden for me and I would give a show."[9]:256 After returning from a tour of overseas bases, the Regimental Hostess at one camp wrote to Jolson, "Allow me to say on behalf of all the soldiers of the 33rd Infantry that you coming here is quite the most wonderful thing that has ever happened to us, and we think you're tops, not only as a performer, but as a person. We unanimously elect you Public Morale Lifter No. 1 of the U.S Army."[9]:257

Jolson was officially enlisted in the United Service Organizations (USO), the organization which provided entertainment for American troops who served in combat overseas.[6]:285 While serving in the USO, he received a Specialist rating due to his age, which would permit him to wear a uniform and have the same standing as an officer. During his time entertaining troops he caught malaria and lost a lung.

In 1946, during a nationally broadcast testimonial dinner in New York City, given on his behalf, he received a special tribute from the American Veterans Committee in honor of his volunteer services during WWII.[3] And in 1949, the movie Jolson Sings Again recreated some scenes showing Jolson during his war tours here.[60]

Korean War

In 1950, Michael Freedland[29] writes, when "the United States answered the call of the United Nations Security Council ... and had gone to fight the North Koreans. ... [Jolson] rang the White House again. 'I'm gonna go to Korea,' he told a startled official on the phone. 'No one seems to know anything about the USO, and it's up to President Truman to get me there.' He was promised that President Truman and General MacArthur, who had taken command of the Korean front, would get to hear of his offer. But for four weeks there was nothing. ... Finally, Louis A. Johnson, Secretary of Defense, sent Jolson a telegram. 'Sorry for delay but regret no funds for entertainment-STOP; USO disbanded-STOP.' The message was as much an assault on the Jolson sense of patriotism as the actual crossing of the 38th Parallel had been. 'What are they talkin' about', he thundered. 'Funds? Who needs funds? I got funds! I'll pay myself!'"[29]:283-284

On September 17, 1950, a dispatch from 8th Army Headquarters, Korea, announced, "Al Jolson, the first top-flight entertainer to reach the war-front, landed here today by plane from Los Angeles..." This time, Jolson had shelved plans for a third movie biography along with a TV show and traveled to Korea at his own expense. "[A]nd a lean, smiling Jolson drove himself without letup through 42 shows in 16 days."[57]:46

Before returning to the U.S., General Douglas MacArthur, leader of UN forces, gave him a medallion inscribed "To Al Jolson from Special Services in appreciation of entertainment of armed forces personnel ‑ Far East Command”, with his entire itinerary inscribed on the reverse side.[61] A few months later, "an important bridge, named the Al Jolson Bridge", was used to withdraw the bulk of American troops from North Korea.[62]

Alistair Cooke wrote, "He [Jolson] had one last hour of glory. He offered to fly to Korea and entertain the troops hemmed in on the United Nations precarious August bridgehead. The troops yelled for his appearance. He went down on his knee again and sang 'Mammy', and the troops wept and cheered. When he was asked what Korea was like he warmly answered, 'I am going to get back my income tax returns and see if I paid enough.'"[63]

Entertainer Jack Benny, who went to Korea the following year, noted that an amphitheater in Korea where troops were entertained, was named the "Al Jolson Bowl."[64]

- New U.S.O. movie

Just 10 days after he returned from Korea, he had agreed with R.K.O. producers Jerry Wald and Norman Krasna to star in a new movie, Stars and Stripes for Ever, about a U.S.O. troupe in the South Pacific during World War II. The screenplay was to be written by Herbert Baker, writer of the 1980 version of The Jazz Singer starring Neil Diamond. The film was to costar singer Dinah Shore.[65]

But just two weeks after the agreement, Jolson died suddenly of a heart attack in San Francisco, due partly to the physical exertion he suffered in Korea. He was survived by his wife and their two recently adopted children. A few months after his death, Defense Secretary George Marshall presented the Medal of Merit to Jolson, "to whom this country owes a debt which cannot be repaid". The medal, carrying a citation noting that Jolson's "contribution to the U.N. action in Korea was made at the expense of his life", was presented to Jolson's adopted son as Jolson's widow looked on.[46]:284

Death and commemoration

The dust and dirt of the Korean front, from where he had returned a few weeks earlier, had settled in his right lung and he was close to exhaustion. While playing cards in his suite at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, Jolson collapsed and died of a massive heart attack on October 23, 1950. His last words were said to be "Boys, I'm going.".[66] He was 64.

After his wife received the news of his death by phone, she went into shock, and required family members to stay with her. At the funeral, police estimated upwards of 20,000 people showed up, despite threatened rain. It became one of the biggest funerals in show business history.[9]:300 Celebrities paid tribute: Bob Hope, speaking from Korea via short wave radio, said the world had lost "not only a great entertainer, but also a great citizen." Larry Parks said that the world had "lost not only its greatest entertainer, but a great American as well. He was a casualty of the [Korean] war." Scripps-Howard newspapers drew a pair of white gloves on a black background. The caption read, "The Song Is Ended."[9]:300

Newspaper columnist and radio reporter Walter Winchell said,

- "He was the first to entertain troops in World War Two, contracted malaria and lost a lung. Then in his upper sixties he was again the first to offer his singing gifts for bringing solace to the wounded and weary in Korea.

- "Today we know the exertion of his journey to Korea took a greater toll of his strength than perhaps even he realized. But he considered it his duty as an American to be there, and that was all that mattered to him. Jolson died in a San Francisco hotel. Yet he was as much a battle casualty as any American soldier who has fallen on the rocky slopes of Korea … A star for more than 40 years, he earned his most glorious star rating at the end — a gold star."[67]

Friend George Jessel said during part of his eulogy,

The history of the world does not say enough about how important the song and the singer have been. But history must record the name Jolson, who in the twilight of his life sang his heart out in a foreign land, to the wounded and to the valiant. I am proud to have basked in the sunlight of his greatness, to have been part of his time.[68]

- Memorial

He was interred in the Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. According to Cemetery Guide, Jolson’s widow purchased a plot at Hillside and commissioned his mausoleum to be designed by well-known black architect Paul Williams. The six-pillar marble structure is topped by a dome, next to a three-quarter-size bronze statue of Jolson, eternally resting on one knee, arms outstretched, apparently ready to break into another verse of “Mammy”. The inside of the dome features a huge mosaic of Moses holding the tablets containing the Ten Commandments, and identifies Jolson as “The Sweet Singer of Israel” and “The Man Raised Up High”. On the day he died, Broadway dimmed its lights in Jolson's honor, and radio stations all over the world were paying tributes. Soon after his passing, the BBC presented a special program entitled Jolson Sings On. His death unleashed tributes from all over the world, including a number of eulogies from friends, including George Jessel, Walter Winchell, and Eddie Cantor.[69] He contributed millions to Jewish and other charities in his will.[70]

In October, 2008, a new documentary film, Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer, premiered at the 50th Lübeck Nordic Film Days, Lübeck, Germany, and won 1st Prize at an annual film competition in Kiel a few weeks later.[71] In November, 2007, a similar documentary, A Look at Al Jolson, was winner at the same festival.[72] Jolson's music remains very popular today both in America and abroad with numerous CDs in print.[73]

Jolson has three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame:

- 6622 Hollywood Blvd. for his contribution to motion pictures

- 1716 Vine St. for his mark on the recording industry

- 6750 Hollywood Blvd. for his achievements in radio

Forty-four years after Jolson's death, the United States Postal Service honored him by issuing a postage stamp. The 29-cent stamp was unveiled by Erle Jolson Krasna, Jolson's fourth wife, at a ceremony in New York City's Lincoln Center on September 1, 1994. This stamp was one of a series honoring popular American singers, which included Bing Crosby, Nat King Cole, Ethel Merman, and Ethel Waters. And in 2006, Jolson had a street in New York named after him with the help of the Al Jolson Society.

Legacy and influence

According to music historians Bruce Crowther and Mike Pinfold: "During his time he was the best known and most popular all-around entertainer America (and probably the world) has ever known, captivating audiences in the theatre and becoming an attraction on records, radio, and in films. He opened the ears of white audiences to the existence of musical forms alien to their previous understanding and experience ... and helped prepare the way for others who would bring a more realistic and sympathetic touch to black musical traditions."[74] Black songwriter Noble Sissle, in the 1930s, said "[h]e was always the champion of the Negro songwriter and performer, and was first to put Negroes in his shows". Of Jolson's "Mammy" songs, he adds, "with real tears streaming down his blackened face, he immortalized the Negro motherhood of America as no individual could."[75]

A few of the people and places that have been influenced by Jolson:

- Irving Berlin

- As the movies became a vital part of the entertainment industry, Berlin was forced to "reinvent himself as a songwriter". Biographer Laurence Bergreen wrote that Berlin's music was "Too old fashioned for progressive Broadway, his music was thoroughly up-to-date in conservative Hollywood." He had his earliest piece of luck in the first sound picture, The Jazz Singer, where Jolson performed his song "Blue Skies".[76] In 1930, he wrote the music for Jolson's fourth movie, Mammy, which included hit songs such as "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy", "Pretty Baby", and "Mammy".

- Judy Garland

- Garland had performed a tribute to Jolson in her concerts of 1951 at the London Palladium and at New York's Palace Theater. Both concerts were to become "central to this first of her many comebacks, and centered around her impersonation of Al Jolson... performing "Swanee" in her odd vocal drag of Jolson."[77] Watch

- Bing Crosby

- Music historian Richard Grudens writes that Kathryn Crosby cheerfully reviewed the chapter about her beloved Bing and his inspiration, Al Jolson. . .where Bing had written, "His chief attribute was the sort of electricity he generated when he sang. Nobody in those days did that. When he came out and started to sing, he just elevated that audience immediately. Within the first eight bars he had them in the palm of his hand."[74] In Crosby's Pop Chronicles interview, he fondly recalled seeing Jolson perform and praised his "electric delivery".[3]

- Crosby's biographer Gary Giddins wrote of Crosby's admiration for Jolson's performance style: "Bing marveled at how he seemed to personally reach each member of the audience." Crosby once told a fan, "I'm not an electrifying performer at all. I just sing a few little songs. But this man could really galvanize an audience into a frenzy. He could really tear them apart."[78]

- Tony Bennett

- "My father... took us to see one of the first talking pictures, The Singing Fool, in which Al Jolson sang "Sonny Boy". In a way, you could say that Jolson was my earliest influence as a singer. I was so excited by what I saw that I spent hours listening to Jolson and Eddie Cantor on the radio. In fact, I staged my first public performance shortly after seeing that movie... to imitate Jolson... I leaped into the living room and announced to the adults, who were staring at me in amazement, 'Me Sonny Boy!' The whole family roared with laughter."[79]

- Neil Diamond

- Journalist David Wild writes that the 1927 movie The Jazz Singer, would mirror Diamond's own life, "the story of a Jewish kid from New York who leaves everything behind to pursue his dream of making popular music in Los Angeles". Diamond says it was "the story of someone who wants to break away from the traditional family situation and find his own path. And in that sense, it 'is' my story." In 1972, Diamond gave the first solo concert performance on Broadway since Al Jolson, and starred in the 1980 remake of Jazz Singer, with Laurence Olivier and Lucie Arnaz.[80]

- Jerry Lewis

- Actor and comedian Jerry Lewis starred in a televised version (without blackface) of The Jazz Singer in 1959. Lewis's biographer, Murray Pomerance, writes that "Jerry surely had his father in mind when he remade the film", adding that Lewis himself "told an interviewer that his parents had been so poor that they could not afford to give him a bar mitzvah." In 1956, Lewis recorded "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby".[81]

- Eddie Fisher

- On a tour of the Soviet Union with his then wife, Elizabeth Taylor, Fisher wrote in his autobiography that "Khrushchev's mistress asked me to sing... I was the first American to be invited to sing in the Kremlin since Paul Robeson. The next day the Herald-Tribune headlines [read] 'Eddie Fisher Rocks the Kremlin'. I gave them my best Jolson: "Swanee", "April Showers" and finally "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody". I had the audience of Russian diplomats and dignitaries on their feet swaying with me."[82]:80 In 1951, Fisher dedicated his "smash hit" song, "Good-bye, G.I. Al," to Jolson, and presented a copy personally to Jolson's widow.[83]

- Bobby Darin

- Darin's biographer, David Evanier, writes that when Darin was a youngster, stuck at home because of rheumatic fever, "[h]e spent most of the time reading and coloring as well as listening to the big-band music and Jolson records... He started to do Jolson imitations... he was crazy about Jolson." Darin's manager, Steve Blauner, who also became a movie producer and vice president of Screen Gems, likewise began his career "as a little boy doing Al Jolson imitations after seeing The Jolson Story 13 times ..."[84]:58

- Ernest Hemingway

- In his memoirs, A Movable Feast, Ernest Hemingway wrote that "Zelda Fitzgerald... leaned forward and said to me, telling me her great secret, 'Ernest, don't you think Al Jolson is greater than Jesus?'" [85]:186

- State of California

- According to California historians Stephanie Barron and Sheri Bernstein, "few artists have done as much to publicize California as did Al Jolson" who performed and wrote the lyrics for "California, Here I Come".[86] It is considered the unofficial song of the Golden State.[87]

- Mario Lanza

- Mario Lanza's biographer, Armando Cesari, writes that Lanza's "favorite singers included Al Jolson, Lena Horne, Tony Martin and Toni Arden."[88]

- Jerry Lee Lewis

- According to singer and songwriter Jerry Lee Lewis, "there were only four true American originals: Al Jolson, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, and Jerry Lee Lewis."[89] "I loved Al Jolson," he said. "I still got all of his records. Even back when I was a kid I listened to him all the time."[90]

- Rod Stewart

- British singer and songwriter Rod Stewart, during an interview in 2003, was asked, "What is your first musical memory?" Stewart replied: "Al Jolson, from when we used to have house parties around Christmas or birthdays. We had a small grand piano and I used to sneak downstairs... I think it gave me a very, very early love of music."[91]

- David Lee Roth

- Songwriter and lead singer of the rock group Van Halen, was asked during an interview in 1985, "When did you first decide that you wanted to go into show business?" He replied, "I was seven. I said I wanted to be Al Jolson. Those were the only records I had -- a collection of the old breakable 78s. I learned every song and then the moves, which I saw in the movies."[92]

- Jackie Wilson

- African-American singer Jackie Wilson recorded a tribute album to Jolson, You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet, which included his personal liner note, "...the greatest entertainer of this or any other era... I guess I have just about every recording he's ever made, and I rarely missed listening to him on the radio.... During the three years I've been making records, I've had the ambition to do an album of songs, which, to me, represent the great Jolson heritage.. [T]his is simply my humble tribute to the one man I admire most in this business... to keep the heritage of Jolson alive."[93]

Filmography

- Mammy's Boy (1923) (unfinished)

- A Plantation Act (1926)

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- The Singing Fool (1928)

- Hollywood Snapshots No. 11 (1929) (short subject)

- Sonny Boy (1929) (Cameo)

- Say It with Songs (1929)

- New York Nights (1929) (Cameo)

- Mammy (1930)

- Show Girl in Hollywood (1930) (Cameo)

- Big Boy (1930)

- Hallelujah, I'm a Bum (1933)

- Wonder Bar (1934)

- Go Into Your Dance (1935)

- Paramount Headliner: Broadway Highlights No. 1 (1935) (short subject)

- The Singing Kid (1936)

- Hollywood Handicap (1938) (short subject)

- Rose of Washington Square (1939)

- Hollywood Cavalcade (1939)

- Swanee River (1939)

- Rhapsody in Blue (1945) (brief scene with Jolson in blackface introducing "Swanee")

- The Jolson Story (1946) (double and singing voice for Larry Parks with brief onscreen appearance)

- Screen Snapshots: Off the Air (1947) (short subject)

- Jolson Sings Again (1949) (singing voice for Larry Parks)

- Oh, You Beautiful Doll (1949) (voice only)

- Screen Snapshots: Hollywood's Famous Feet (1950) (short subject) (narrator)

- Memorial to Al Jolson, (1951) documentary — Columbia Pictures

- The Great Al Jolson, (1955) documentary, Columbia Pictures

Theater

- La Belle Paree (1911)

- Vera Violetta (1911)

- The Whirl of Society (1912)

- The Honeymoon Express (1913)

- Children of the Ghetto (before 1915)

- Robinson Crusoe, Jr. (1916)

- Sinbad (1918)

- Bombo (1921)

- Big Boy (1925)

- Artists and Models of 1925 (1925) (added to cast in 1926)

- Big Boy (1926) (revival)

- The Wonder Bar (1931)

- Hold on to Your Hats (1940)

Famous songs

- That Haunting Melodie (1911) Jolson's first hit.

- Ragging the Baby to Sleep (1912)

- The Spaniard That Blighted My Life (1912)

- That Little German Band (1913)

- You Made Me Love You (1913)

- Back to the Carolina You Love (1914)

- Yaaka Hula Hickey Dula (1916)

- I Sent My Wife to the Thousand Isles (1916)

- I'm All Bound Round With the Mason Dixon Line (1918)

- Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody (1918)

- Tell That to the Marines (1919)

- I'll Say She Does (1919)

- I've Got My Captain Working for Me Now (1919)

- Swanee (1919)

- Avalon (1920)

- O-H-I-O (O-My! O!) (1921)

- April Showers (1921)

- Angel Child (1922)

- Coo Coo' (1922)

- Oogie Oogie Wa Wa (1922)

- That Wonderful Kid From Madrid (1922)

- Toot, Toot, Tootsie (1922)

- Juanita (1923)

- California, Here I Come (1924)

- I Wonder What's Become of Sally? (1924)

- All Alone (1925)

- I'm Sitting on Top of the World (1926)

- When the Red, Red Robin (Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin' Along) (1926)

- My Mammy (1927)

- Back in Your Own Backyard (1928)

- There's a Rainbow 'Round My Shoulder (1928)

- Sonny Boy (1928)

- Little Pal (1929)

- Liza (All the Clouds'll Roll Away) (1929)

- Let Me Sing and I'm Happy (1930)

- The Cantor (A Chazend'l Ofn Shabbos) (1932)

- You Are Too Beautiful (1933)

- Ma Blushin' Rosie (1946)

- Anniversary Song (1946)

- Alexander's Ragtime Band (1947)

- Carolina in the Morning (1947)

- About a Quarter to Nine (1947)

- Waiting for the Robert E. Lee (1947)

- Golden Gate (1947)

- When You Were Sweet Sixteen (1947)

- If I Only Had a Match (1947)

- After You've Gone (1949)

- Is It True What They Say About Dixie? (1949)

- Are You Lonesome Tonight? (1950)

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Stars over Broadway. PBS.org.

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William (1950-10-23). "All Music Guide entry". Allmusic.com. http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=41:80924. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Gilliland, John. Pop Chronicles the 40's: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40's. ISBN 9781559351478. OCLC 31611854., cassette 3, side B.

- ↑ Dix, Andrew and Taylor, Jonathan. Figures of Heresy, Sussex Academic Press (2006), pg. 176; quoted from Dylan's book, Biograph (1985)

- ↑ Bainbridg, Beryl. Front Row: Evenings at the Theatre, Continuum International Publishing (2005), pg. 109

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 Oberfirst, Robert, Al Jolson, You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet, (1980) Barnes & Co., London

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Kenrick, John. "Al Jolson: A Biography" Musicals101.com. 2003.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Zolotow, Maurice. "Ageless Al." Reader's Digest. January, 1949.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 Goldman, Herbert G., Jolson -– the Legend Comes to Life, (1988) Oxford Univ. Press

- ↑ "Benefit Performance: 'Bombo' to Be Given at Century in Aid of Jewish War Sufferers" New York Times, March 10, 1922

- ↑ "AL JOLSON WELCOMED BACK.; He Returns to the Winter Garden in "Bombo," With New Jokes." New York Times, May 15, 1923

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Rowland-Warne, L. (2000-06-01). "Eyewitness: Costume". DK CHILDREN. http://www.amazon.com/Eyewitness-Costume-L-Rowland-Warne/dp/0789455862/ref=si3_rdr_bb_product. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Oxford University Press. 1993.[1]

- ↑ Granville Ganter, "He made us laugh some": Frederick Douglass's humor, originally published in African American Review, December 22, 2003. Online at HighBeam Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ↑ C. Wittke, Tambo and Bones: A History of the American Minstrel Stage (1930, repr. 1968).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Alexander, Michael. Jazz Age Jews, Princeton University Press (2003)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Norwood, Stephen Harlan, and Pollack, Eunice G. Encyclopedia of American Jewish History, ABC-CLIO, Inc. (2008)

- ↑ "''African American Registry''". Aaregistry.com. http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/2207/The_Ku_Klux_Klan_a_brief__biography. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Ciolino, Joseph, "Al Jolson Wasn’t Racist!"Black Star News, May 22, 2007

- ↑ Freedland, Michael. "You couldn't have Al Jolson any other way" Timesonline, Feb. 27, 2009

- ↑ Hill, Anthony Duane. "Anderson, Garland (1886-1939)" Black Past.org.

- ↑ "''Gioia, Ted, ''New York Times'', October 22, 2000". Ferris.edu. http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/links/jolson/. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ "Tap Dance Hall of Fame". Atdf.org. http://www.atdf.org/awards/legon.html. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Frank, Rusty E. Tap! The Greatest Tap Dance Stars and Their Stories, 1900 – 1955, Da Capo Press (1995)

- ↑ "Past/Present/Future for … Brian Conley." What's on Stage, June 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Al Jolson Society Official Website". Jolson.org. http://www.jolson.org/. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ Gulla, Bob. Icons of R&B and Soul: An Encyclopedia of the Artists, Greenwood Press (2008) p. 133

- ↑ Baraka, Amiri (as LeRoi Jones), Blues People: Negro Music in White America, (1963) Morrow

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Freedland, Michael. Jolson - The Story of Al Jolson (1972, 2007)

- ↑ Kusinitz, Kevin. "Celebrity Endorsements." The Daily Standard, May 23, 2008.

- ↑ King, Alan. Name Dropping, Simon and Schuster (1997)

- ↑ Shepherd, John. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Continuum International Publishing Group (2003)

- ↑ Interview with George Jessel, circa 1980, video — 2 minutes.

- ↑ Hall, Mourdant. New York Times review of The Jazz Singer, Oct. 7, 1927 [2]

- ↑ Epstein, Helen. Joe Papp: An American Life, Da Capo Press (1996) pgs.28-29

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Eyman, Scott. The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution, 1926 – 1930, Simon and Schuster (1997)

- ↑ Berg, A. Scott. Goldwyn: A Biography, Alfred A. Knopf (1998)

- ↑ "This Is Work, Not Play." Newsweek. June 28, 1999

- ↑ Mast, Gerald, and Kawin, Bruce F. A Short History of the Movies, (2006) Pearson Education, Inc.

- ↑ Williams, Linda. Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Top to O. J. Simpson, Princeton University Press (2002)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Carringer, Robert. L. The Jazz Singer (1979) University of Wisconsin Press

- ↑ UCLA Film and Television Archive Newsletter April/May 2002.

- ↑ Kovan, Florice Whyte. Some Notes on Ben Hecht's Civil Rights Work, the Klan and Related Projects BenHechtBooks.net.

- ↑ Hall, Mourdaunt. New York Times. February 9, 1933. p. 15.

- ↑ Gilliatt, Penelope. New Yorker. June 23, 1973.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Fisher, James. Al Jolson — a Bio-bibliography (1994)

- ↑ Abel, Variety. March 6, 1934.

- ↑ "At the University", Harvard Crimson, May 21, 1934.

- ↑ Calloway, Cab. Of Minnie the Moocher & Me, Thomas Y. Crowell Company (1976)

- ↑ Nugent, Frank S., New York Times, May 6, 1939 p.21

- ↑ Abel. Variety. May 10, 1939, p. 14

- ↑ "The Jolson Story" review, Liberty, Oct. 19, 1946

- ↑ "A Tribute by Larry Parks" Jolsonville

- ↑ Variety, Sept. 18, 1946, p. 16

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Gabbard, Krin. Jammin' at the Margins, (1996) University of Chicago Press

- ↑ Custen, George. Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public History, (1992) Rutgers University Press

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Abramson, Martin, The Real Story of Al Jolson. 1950.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Woolf, S.J. "Army Minstrel." New York Times. September 27, 1942.

- ↑ Morehouse, Ward. Hartford Courant, September 20, 1942

- ↑ "Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hC8ZmBIouzQ. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Cosmopolitan Magazine, January 1951.

- ↑ Dutton, John. The Forgotten Punch in the Army's Fist: Korea 1950-1953, Ken Anderson, (2003), p. 98

- ↑ Cooke, Alistair. "Al Jolson dies on crest of a wave." The Guardian (UK). October 25, 1950.

- ↑ Livingstone, Mary. Jack Benny, Doubleday (1978) p. 184-185

- ↑ "Jolson to Return to Screen at R.K.O." New York Times, October 11, 1950

- ↑ Jolson in Korea, Video, 9 min

- ↑ Winchell, Walter. A Song for Al Jolson. jolsonville.com. October, 1950

- ↑ Jessel, George (1950-10-26). "The Majesty of Jolie". Archived from the original on 2008-10-27. http://jolsonville.com/eulogies/by-george-jessel/.

- ↑ "''Al Jolson Tribute'' site". Jolsonville.com. http://jolsonville.com/. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Brody, Seymour (1996). "Al Jolson". Jewish Heroes & Heroines of America : 150 True Stories of American Jewish Heroism. Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/jolson.html. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer wins 1st Prize Nov. 15, 2008

- ↑ A Look at Al Jolson, winner at German film festival November, 2007

- ↑ "Al Jolson: Music". Amazon.com. http://www.amazon.com/s?url=search-alias%3Dpopular&field-keywords=Al+Jolson. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Crowther, Bruce, and Pinfold, Mike. Singing Jazz: The Singers and Their Styles, Hal Leonard Corp. (1997)

- ↑ Knight, Arthur. Disintegrating the Musical: Black Performance and American Musical film, Duke Univ. Press (2002)

- ↑ Bergreen, Laurence. As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin, Da Capo Press (1996)